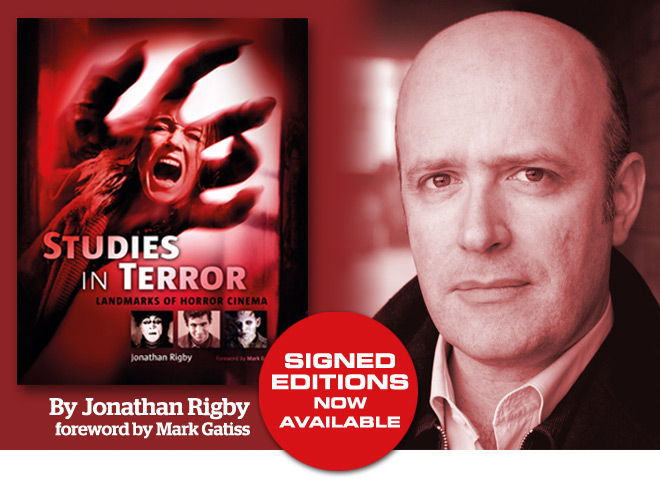

Studies in Terror: Landmarks of Horror Cinema is the latest book by Jonathan Rigby, the author of the classic genre histories English Gothic and American Gothic.

The new book was launched at two recent events. At Londons Cinema Museum on Friday 7 October Jonathan joined Kim Newman (who was promoting the latest edition of his book Nightmare Movies) for the on-stage discussion ‘From Hammer to Chainsaw’, in which they dissected horror films of the 1960s and 70s. On Tuesday 11 October, Jonathan was joined by Mark Gatiss for a Screen Talk at the prestigious Barbican Cinema. They discussed Studies in Terror (for which Mark wrote the foreword) as well as their recent collaboration on the BBC documentary series A History of Horror.

Studies in Terror is available now from the Signum on-line shop, as well as all good book retailers. We asked Jonathan a few questions about the book SFX magazine has hailed as “erudite”, “idiosyncratic” and “refreshingly intelligent” …

The criteria for English Gothic and American Gothic were both pretty clear. How did you choose the 130 films you appraise in Studies in Terror?

Well, I wanted the book to function in part as an informal history of horror cinema in general, so to a certain degree the choices were based on the idea of giving the reader an overview. But, more importantly, I felt strongly that another standard-issue, entry-level horror history is something nobody needs. The book had to have a personal slant. So, rather than get together all the ‘usual suspects’ Alien, A Nightmare on Elm Street etc etc I happily included a generous assortment of so-called ‘guilty pleasures’ instead.

Which isn’t to say that plenty of the standard titles aren’t included. They just had to be films that stimulated me and which I could say something new about. And certainly the big-name horror directors are by no means skimped on; Terence Fisher and Mario Bava, for example, get four films apiece.

I was also keen to emphasise the genre’s international scope. There are a lot of American films in there inevitably, I think, as that’s been the overwhelming bias of film presentation ever since Hollywood acquired its dominant position around 1918. But there’s also a wide range of foreign-language films too, which is absolutely essential to presenting a balanced view.

The book has only just come out, but already some of your choices have been described as surprising. Why, for example, have you written about The Exorcist III, but not the first film in the series?

I think my previous answer goes some way towards explaining this. And, let’s face it. I don’t think The Exorcist is likely to suffer much from its exclusion by me! After all, its a film pretty much everybody knows about – and which horror fans know an awful lot about. And because the main entries are accompanied by a kind of running commentary on genre developments, the importance of the film isn’t exactly ignored in the course of the book.

The Exorcist III, by contrast, is a film very few people know about. Its very good on several levels and happens to contain one of the most immaculately executed scare scenes in the genre. And, because the book is focused on shocking, scary or disturbing moments from the films in question, that scene was justification in itself.

What are the most obscure films in the book?

There are several I could mention, but some of the Mexican ones are pretty rare. El libro de piedra, for example, is a film I suspect most horror fans have never heard of. Yet its director, Carlos Enrique Taboada, is considered a master of horror in his native Mexico, and the film itself is sufficiently famous there to have been remade recently. But outside Mexico? Virtually unknown.

There are plenty of other titles which, though not unknown, are normally marginalised. Il castello dei morti vivi, for instance, is a lovely Grimm-type fairy tale that’s only mentioned in horror histories when writers erroneously claim that it was directed by an Italian (rather than an American in Italy) – a mistake, incidentally, which survives to this day on the IMDb. And the film is only mentioned elsewhere when mainstream journalists snigger about the fact that, early in his career, Donald Sutherland appeared in a piece of rubbish called Castle of the Living Dead. Needless to say, these people have never seen the ‘piece of rubbish’ in question.

Are horror films now taken seriously by critics, or do you feel that many films remain undervalued?

Theres still a lot of condescension around. And I certainly agree with Leonard Wolf when he said that, “We need a more inclusive definition of greatness.” (He was discussing the literary status of Dracula at the time.)

But I think critics are more aware nowadays of the genre’s importance as a cultural barometer of what frightens people at any given time. And it may only be because of political correctness – but critics are certainly far less inclined these days to describe horror fans as subnormal, which used to happen quite often. So thats something, I suppose.

However, it would be disastrous if horror were ever to become completely respectable. That would take away much of the fun – and, indeed, the point!